In the mid-1800s, the first Chinese immigrants arrived in the US, fleeing the threat of famine that plagued drought-struck China at the time, and seeking stability. The promise of the Gold Rush and railroad construction industry brought these hopeful laborers to cities all along the West Coast, settling initially in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle.

By the 1880s, the Chinese American population saw their first major peak, making up approximately .21% of the total population, spreading across the country from Butte, Montana, to New York City.

This first wave of immigrants soon found that they were not welcome in their new homes, from hostility they faced in their immediate neighborhoods all the way up to the US federal government. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring all Chinese laborers from entering the country. To this day, the Chinese Exclusion Act remains the only restriction of immigration for a specific nationality in the country's history.

The result of these exclusionary laws was the formation of the country's first "Chinatowns," defined as any towns outside Asia where the population is predominantly Chinese.

"Because of the initial disadvantages associated with immigrant status, immigrants tended to form their own ethnic enclaves," Min Zhou, a professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies at UCLA, told Insider. "They had nowhere else to go."

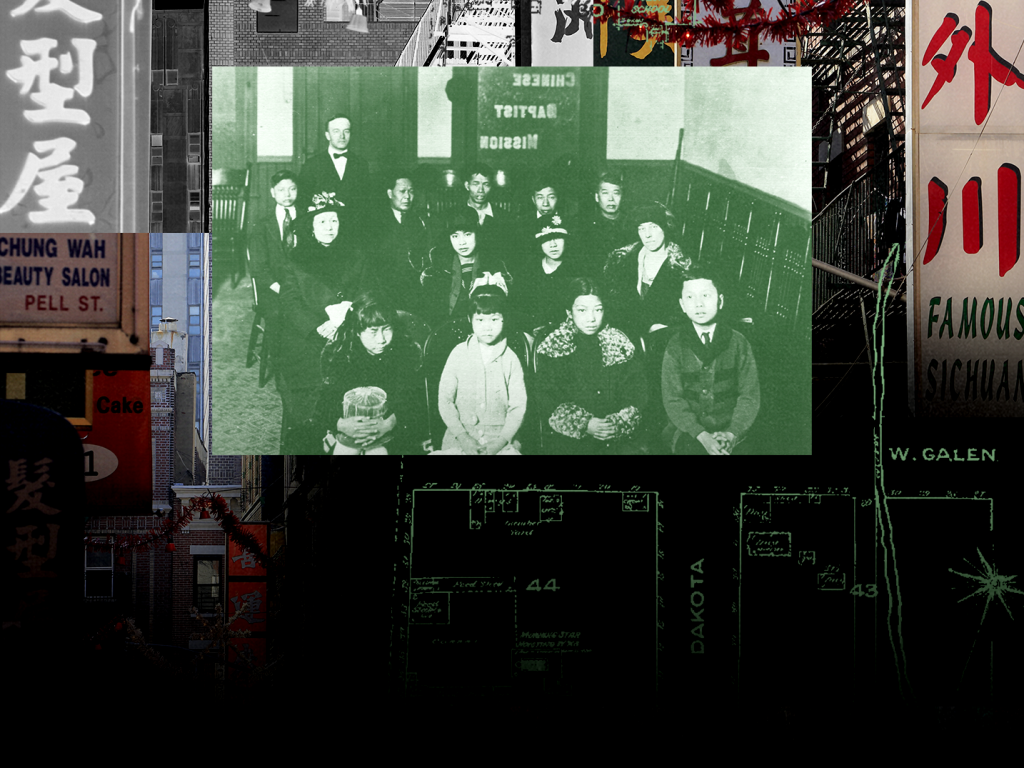

Several prominent, urban Chinatowns that formed in the 1880s continue to evolve and thrive today, the most notable being the Chinatown in Manhattan, New York, which holds the distinction of being the largest in the country, and the Chinatown in San Francisco, California, which is thought to be the oldest. Countless other Chinatowns, however, did not survive. Many were forced to relocate or were destroyed by acts of arson. Most, however, experienced a natural decline in population after the slowdown of their respective labor industries, including mining and railroad construction. Some of these early Chinatowns have completely vanished, while others still show subtle reminders of their past: a derelict paifang gate left standing, faded Chinese characters on abandoned buildings.

In Butte, Montana, generations of restaurant owners and shop keepers work tirelessly to preserve their family legacies, even when the Chinese American population in the town is on a decline. In Detroit, Michigan, a Chinatown that all but disappeared is now being pieced back together by artists and activists. And in Atlanta, Georgia, a nondescript strip mall has become an oasis for Asian Americans in the South. Each Chinatown highlights the unique challenges and triumphs of being Asian in this country, and the often overlooked stories of American history.

Butte, Montana

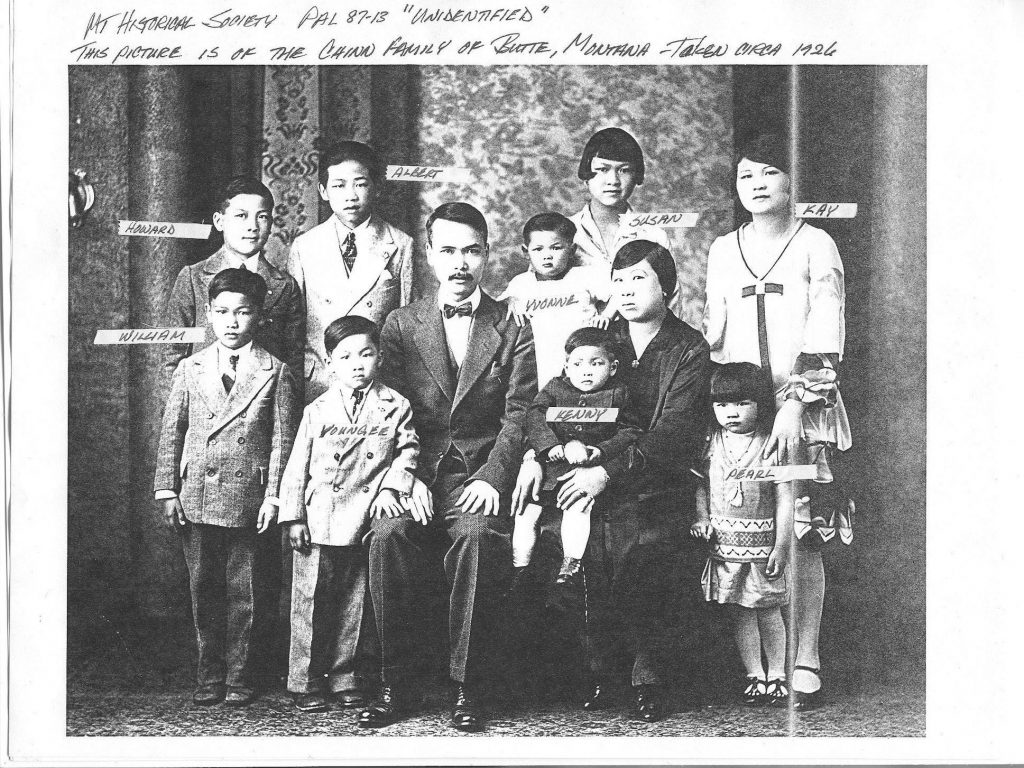

The Chinns were among the first Chinese immigrants to settle in Butte, Montana, starting with the arrival of Chin Hin Doon in 1875.

By 1894, he had joined Wah Chong Tai, a Seattle-based Chinese mercantile for trading imported goods, including cigars, herbs, and pangolin scales. Five years later, the mercantile expanded into a larger building. Complete with small individual shop booths with private entrances, this new building housed other Chinese immigrant businesses, including herbalists, tailors, and specialty shops. Together, these beginnings allowed a vibrant Chinatown to thrive in Southwest Montana.

Jerry Tam, third-generation owner and operator of Pekin Noodle Parlor, returned home to help with the restaurant in 2009 after his mother had a stroke. He took over completely after the passing of his father, Danny Wong-Tam, in 2020. Throughout the pandemic, Tam fought to keep the restaurant running, managing a five-person operation and upholding the restaurant's reputation with locals as "open through anything."

Due to concerted efforts from residents like Tam and Stonehocker, Butte Chinatown's memories, culture, and people continue to remain vivid in local and even national memory. This is not without its share of difficulties: the impressive age of the Pekin is also the root of many of the issues Tam grapples with today. With the transfer of ownership from his father to him, the city health department is requiring the restaurant's centuries-old kitchen, wooden shelving units, and flooring to all be replaced. "There isn't any PPP money coming our way. There are no loans, no grant money," said Tam. "I'm on a teeter totter of saying, if it's going to cost a certain amount, I'm sorry, but we may finally have to close."

Detroit, Michigan

The first few Chinese washermen arrived to Detroit in the 1880s. A wave of Chinese business-owning families, including the Yee, Chin, and Chung families, followed soon after.

Together, these first arrivals settled into the area and soon opened restaurants, grocery stores, hand laundries, and even a Chinese school.

Chung's Chop Suey operated for over 80 years before closing for good in 2000, long after the majority of residents had abandoned the area. Most left after a series of violent crimes in the 1970s and 1980s, including the holdup robbery and homicide of restaurant owner Tommie Lee in 1970 and the murder of Vincent Chin later in 1982. The Detroit Free Press reported that by 1989, only about 100 Chinese residents remained in the neighborhood. "If they had left Chinatown where it was, it probably would have developed into a Greektown," Philip Chung, then co-owner of Chung's Restaurant, told the Free Press at the time. "We never saw this area have a heyday, but we saw it go from not-too-bad to worse."

Despite the turbulent history of Detroit's Chinatown, people who lived there still vividly remember it as a safe gathering space for the community. Curtis Chin, great-grandson of Joe, spent his childhood in the back kitchen of Chung's. "I saw all of Detroit come through our restaurant, from the old Chinese bachelors, to the pimps and prostitutes, to the mayor. I think that's a beautiful thing about Chinese restaurants and Chinatowns in particular; that they're so popular and really one of the few places in our country where you can see a cross section of people. Where we can all still connect."

Chien-An Yuan, an artist and activist based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is one of many leaders seeking to revive that sense of connection through various revitalization initiatives related to Detroit's Chinatown. One of his principal projects in development is a cultural night market, with the goal of facilitating collaboration between local organizations and providing a regular gathering space for the surrounding community.

Yuan noted that settling on plans and managing relationships between multiple organizational stakeholders has proven difficult. Earlier this year, during the planning period for the Vincent Chin 40th Remembrance and Rededication, an event aimed to honor Chin's legacy and combat anti-Asian hate, a local organization's proposal for a memorial protest was met with a cease and desist order. In early August, a meeting between local community leaders and organizations about the night market also ended in a standstill.

Despite the organizational difficulties, one aspect most involved can agree upon is looking forward, rather than back. "Nobody is trying to rebuild the old Chinatown," Yuan said. "But everybody seems to have a different idea of what should come next."

Atlanta, Georgia

Chinatown Square Mall in Chamblee, Georgia — just 14 miles from downtown Atlanta — was built in 1988 as the first Asian mall in the Southeast.

The mall, referred to by many as "Chinatown," occupies a plaza building of just under 55,000 square feet. Located in the suburbs of Atlanta, the building appears as a hybrid of a traditional Chinatown and a suburban strip mall: a striking pagoda-style roof and a monochrome beige facade, store signs in both Mandarin and English, and a parking lot wrapping around three out of the building's four sides.

While the space might not look or feel like a traditional urban Chinatown, it serves many of the same purposes as a cultural community hub for local Chinese residents. The areas surrounding the mall are less densely populated than larger urban Chinatowns, but have notably higher percentages of Asian residents than central Atlanta and the rest of Georgia. Around 30 tenants provide these areas with a diverse array of Asian cuisine, goods, and services, including a comic book store, Atlanta's first Asian BBQ joint, and a translation services agency. Some have been operating since the building's construction, drawing loyal customer bases that have spread business through word of mouth.

A store owner who spoke to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in August 2020 also cited the plaza as an impromptu relief center: "When Hurricane Irma hit Florida in 2017, many displaced Chinese families drove north, searched for Chinatown, and arrived here, where the shop owners sheltered and fed them."

Chinatown Square Mall has become a haven for Asian Americans not only in Georgia, but across the Southeast. Yaqin Cao, a longtime resident of Charlotte, North Carolina, has taken a roughly bi-annual day trip to Atlanta's Chinatown for over 20 years. She first started making the trip when her favorite Asian grocery stores and restaurants in Charlotte closed down. "I'd typically leave between 4 and 5 in the morning, drive for around four hours, and return after a full day of eating and shopping by around midnight." Nowadays, so many of her friends have found out about Atlanta's Chinatown, they sometimes carpool in groups of up to 20 people, filling multiple cars, or even renting out a bus to make the trip.

When asked how she first discovered Atlanta's Chinatown while living in Charlotte, she emphasized the importance of word of mouth endorsements. "Friends told me. Now, I tell friends about it, too. On the internet, I couldn't find information on [Atlanta's Chinatown] and why it was so good," she said. "But when we hear each other talking about it, it's different. We trust each other."

Redefining Chinatown

"The Chinatowns of Butte, Detroit, and Atlanta are atypical, and typical at the same time," said Min Zhou, regarding the unique trajectory of each. "They are atypical, in that they do not reflect common perceptions of Chinatowns today. But they are typical, in that they reflect the complex diversity of the Chinese diaspora."

For these individuals across the country, "Chinatown" has extended beyond its physical borders to become symbolic.

Jerry Tam carries this symbolism with him daily, through a sense of responsibility and pride in continuing his parents' and great-grandparents' operation. "Everytime I walk in the door, it's a reminder of how hard their lives were," he said.

Curtis Chin expresses this symbolism through his craft, beginning with his decision to move to New York City. "As a gay, aspiring writer, Detroit just wasn't the place for me anymore. I had to make the decision to leave." Since then, Chin has directed multiple short films and published several articles about his experiences growing up in Detroit's Chinatown, culminating in the sale of his memoir, "Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant," to Little, Brown and Company, forthcoming in 2023.

And for Yaqin Cao, this symbolism is found through her shared memories of Atlanta's Chinatown with her daughter, Dana Gong. "My childhood trips to Atlanta still represent the ultimate source of comfort for me. We'd wake up so early, with the same type of excitement as waking up early for the airport for vacations as a kid," Gong recalled. "I'd completely knock out in the car. When we'd arrived, I'd know. I'd open my eyes giddy about all the shopping we were about to do and all the cravings we were about to satisfy."

Now a resident of Brooklyn, New York, Gong still carries a particular nostalgia for the mall in Atlanta. Stinky tofu, a Chinese street food and personal favorite of hers, can be pretty difficult to track down, even in Manhattan, she said. "But in Atlanta, I still know exactly where to find it: The Great Wall Super Market off of I-85."

This story is part of a two-part series about the past and future of America's Chinatowns. Read about how the next generation of New York City's Chinatown are working to preserve their families' legacies.

`;

slideSection.insertAdjacentHTML("beforebegin", appendSlides); // heroSection.insertAdjacentHTML("afterbegin", displayHed);

}

// IF ONLY THE HERO IS WORKING, BACKUP else if (heroSection) { const displayHed = `

`;

const config = { attributes: true, childList: true, subtree: true };

const mutationCb = function (mutationsList, observer) { for (const mutation of mutationsList) { // if (mutation.type === "childList") { // console.log("yes") const ct_img = document.querySelector( ".gi-ct div.full-bleed-hero figure.figure.image-figure-image.full-bleed-hero div.aspect-ratio img" );

if (ct_img) { if ( window.matchMedia("(max-width: 768px)").matches && window.matchMedia("(orientation: portrait)").matches ) { ct_img.src = "https://i.insider.com/62e25652536a23001911fd81";

} else { ct_img.src = "https://i.insider.com/62e25652536a23001911fd81"; }

// INSERT ALL THE INTRO TEXT BEFORE THE HEADLINE CONTAINER

fullBleedHero.insertAdjacentHTML("afterbegin", displayHed);

observer.disconnect(); // } }

} };

const observer = new MutationObserver(mutationCb); observer.observe(fullBleedHero, config);

}

}

});